While flicking through a feature on clafoutis in a French cookery magazine recently, I was intrigued to find several recipes for savoury clafoutis amongst the more familiar cherry, apricot and plum versions. Reading on I was keen to find out how a savoury clafoutis differs from the provençal tian, a traditional, vegetable gratin dish with five key elements – rice, cheese, eggs, breadcrumbs and vegetables.

One of the things I love about a tian is its frittata-like texture which makes it light yet satisfying with the inclusion of the rice. It quickly became clear from the savoury clafoutis recipes that the texture would be more dense as milk (or cream), and flour are incorporated into the batter. No rice though!

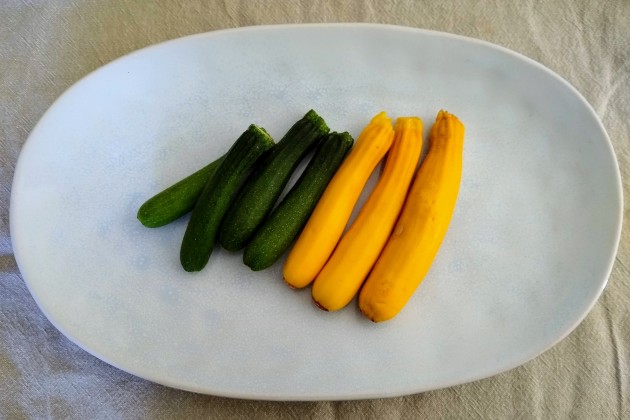

With an endless supply of courgettes from the garden this year and looking for something satisfying for supper on a surprisingly autumnal evening in early September, I had a go at a courgette clafoutis and the recipe is below. I used brown rice flour to make the recipe gluten-free. It was delicious served warm and my husband enjoyed the remaining quarter from his lunchbox the following day.

Clafoutis aux courgettes

Serves two hungry people and I recommend partnering it with a fresh, tomato salad.

You will need a 20cm frying pan

4 medium-sized courgettes, sliced into rounds

2 cloves of garlic, crushed

1 tbsp of chopped rosemary

6 eggs, beaten

50ml milk

75g brown rice flour or other gluten-free flour

Half a 150g goat’s cheese log, sliced into rounds

50g grated emmental cheese

Olive oil

Fry the courgette slices in some olive oil until they are lightly browned and softened, adding the garlic as the courgettes begin to soften. While the courgettes are cooking, mix the flour, rosemary and ¾ of the emmental together in a bowl with a pinch of salt and a couple of turns of the black pepper grinder. Make a well in the middle of the bowl and gradually add the beaten egg, whisking until the mixture becomes a smooth batter.

Add the batter to the courgettes in the frying pan and place the sliced goat’s cheese on the top. Sprinkle with the remaining emmental. Cook the clafoutis on the hob on a medium heat for five minutes or until the mixture starts to brown around the edges. Finish off under a medium to high grill until the top is golden brown.